This second article, which is part of the series on Linux device drivers, deals with the concept of dynamically loading drivers, first writing a Linux driver, before building and then loading it.

As Shweta and Pugs reached their classroom, they were already late. Their professor was already in there. They looked at each other and Shweta sheepishly asked, “May we come in, sir”. “C’mon!!! you guys are late again”, called out professor Gopi. “And what is your excuse, today?”. “Sir, we were discussing your topic only. I was explaining her about device drivers in Linux”, was a hurried reply from Pugs. “Good one!! So, then explain me about dynamic loading in Linux. You get it right and you two are excused”, professor emphasized. Pugs was more than happy. And he very well knew, how to make his professor happy – criticize Windows. So, this is what he said.

As we know, a typical driver installation on Windows needs a reboot for it to get activated. That is really not acceptable, if we need to do it, say on a server. That’s where Linux wins the race. In Linux, we can load (/ install) or unload (/ uninstall) a driver on the fly. And it is active for use instantly after load. Also, it is disabled with unload, instantly. This is referred as dynamic loading & unloading of drivers in Linux.

As expected he impressed the professor. “Okay! take your seats. But make sure you are not late again”. With this, the professor continued to the class, “So, as you now already know, what is dynamic loading & unloading of drivers into & out of (Linux) kernel. I shall teach you how to do it. And then, we would get into writing our first Linux driver today”.

Dynamically loading drivers

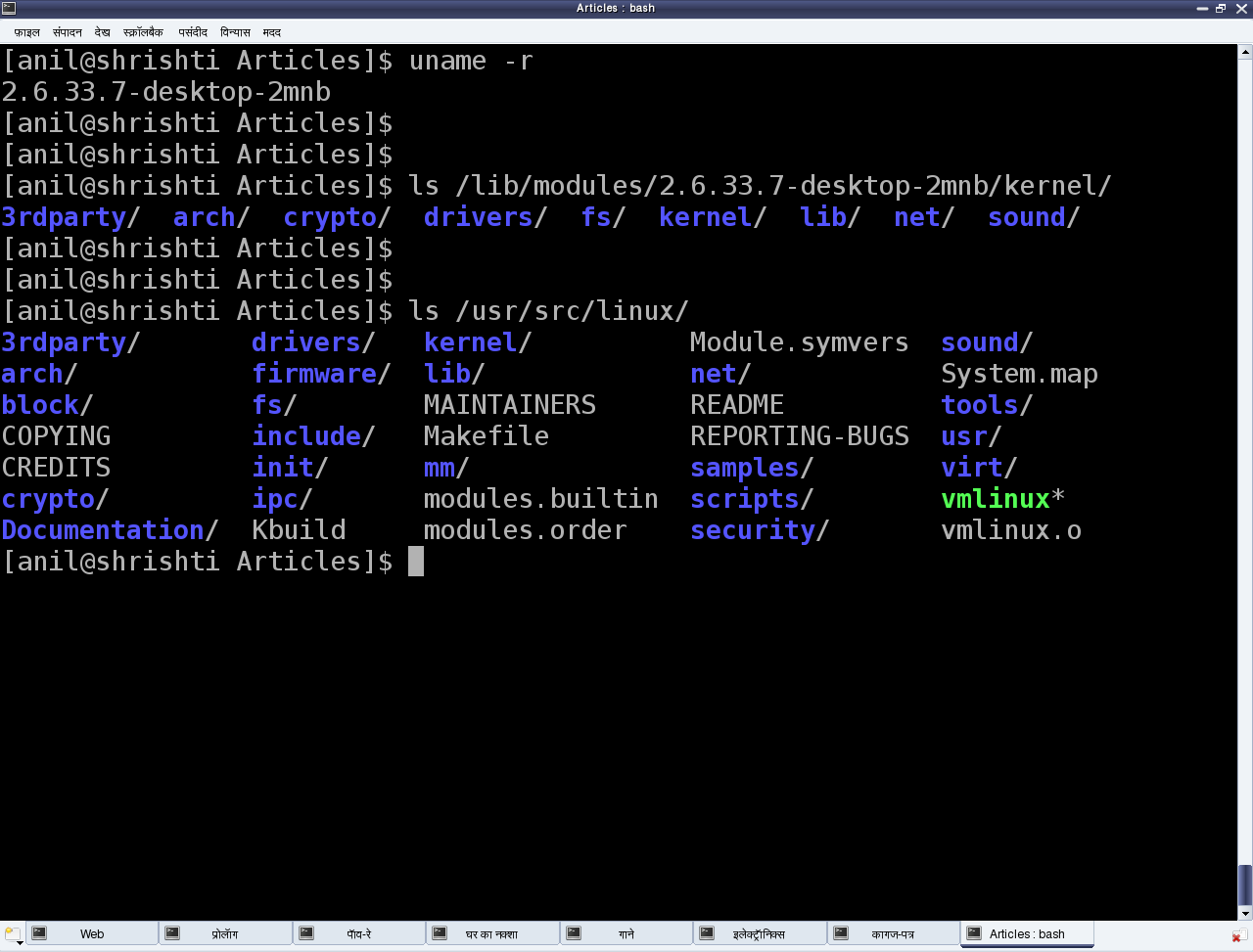

These dynamically loadable drivers are more commonly referred as modules and built into individual files with .ko (kernel object) extension. Every Linux system has a standard place under the root file system (/) for all the pre-built modules. They are organized similar to the kernel source tree structure under /lib/modules/<kernel_version>/kernel, where <kernel_version> would be the output of the command “uname -r” on the system. Professor demonstrates to the class as shown in Figure 4.

Now, let us take one of the pre-built modules and understand the various operations with it.

Here’s a list of the various (shell) commands relevant to the dynamic operations:

- lsmod – List the currently loaded modules

- insmod <module_file> – Insert/Load the module specified by <module_file>

- modprobe <module> – Insert/Load the <module> along with its dependencies

- rmmod <module> – Remove/Unload the <module>

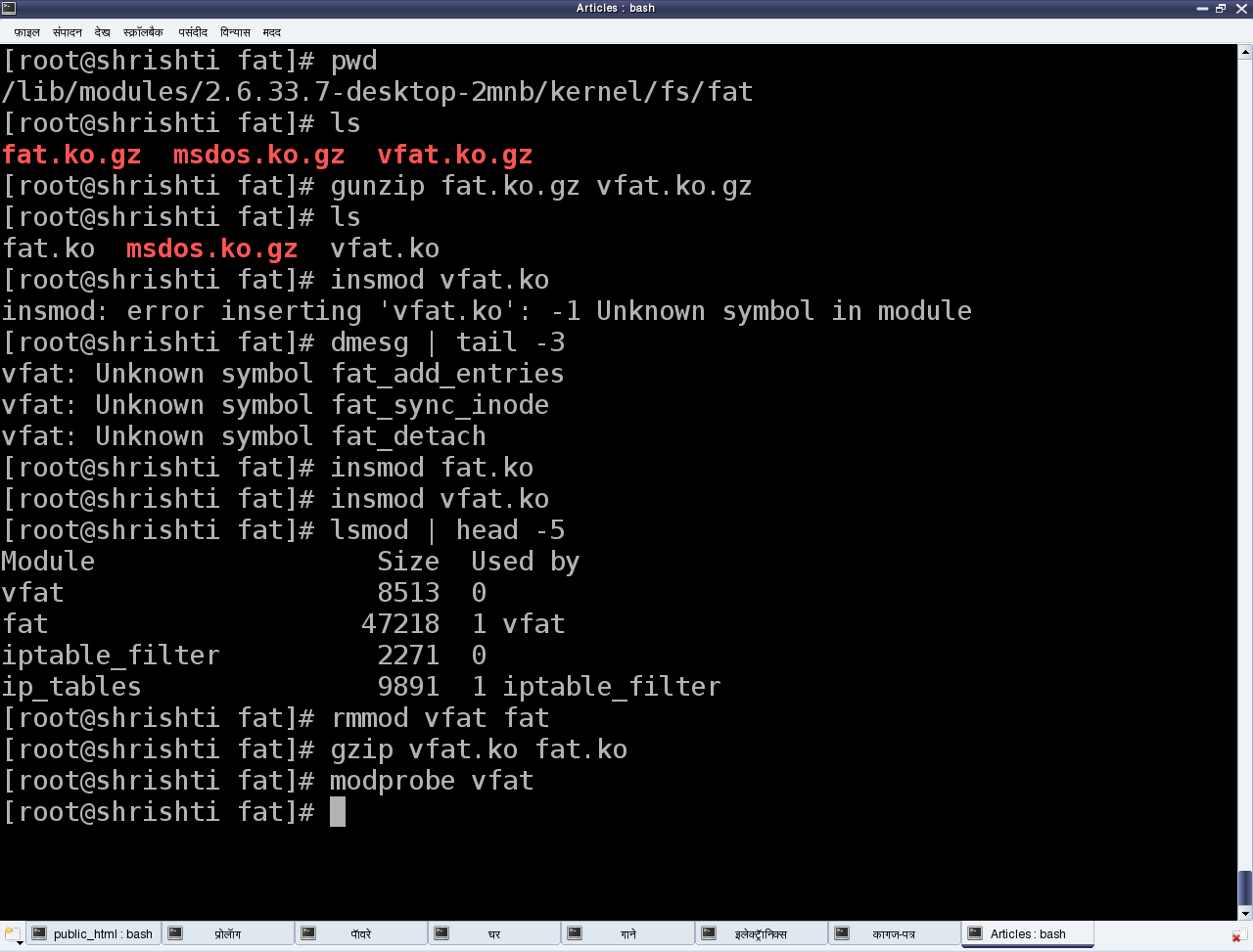

These reside under the /sbin directory and are to be executed with root privileges. Let us take the FAT file system related drivers for our experimentation. The various module files would be fat.ko, vfat.ko, etc. under directories fat (& vfat for older kernels) under /lib/modules/`uname -r`/kernel/fs. In case, they are in compressed .gz format, they need to be uncompressed using gunzip, for using with insmod. vfat module depends on fat module. So, fat.ko needs to be loaded before vfat.ko. To do all these steps (decompression & dependency loading) automatically, modprobe can be used instead. Observe that there is no .ko for the module name to modprobe. rmmod is used to unload the modules. Figure 5 demonstrates this complete experimentation.

Our first Linux driver

With that understood, now let’s write our first driver. Yes, just before that, some concepts to be set right. A driver never runs by itself. It is similar to a library that gets loaded for its functions to be invoked by the “running” applications. And hence, though written in C, it lacks the main() function. Moreover, it would get loaded / linked with the kernel. Hence, it needs to be compiled in similar ways as the kernel. Even the header files to be used can be picked only from the kernel sources, not from the standard /usr/include.

One interesting fact about the kernel is that it is an object oriented implementation in C. And it is so profound that we would observe the same even with our first driver. Any Linux driver consists of a constructor and a destructor. The constructor of a module gets called whenever insmod succeeds in loading the module into the kernel. And the destructor of the module gets called whenever rmmod succeeds in unloading the module out of the kernel. These two are like normal functions in the driver, except that they are specified as the init & exit functions, respectively by the macros module_init() & module_exit() included through the kernel header module.h

/* ofd.c – Our First Driver code */

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/version.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

static int __init ofd_init(void) /* Constructor */

{

printk(KERN_INFO "Namaskar: ofd registered");

return 0;

}

static void __exit ofd_exit(void) /* Destructor */

{

printk(KERN_INFO "Alvida: ofd unregistered");

}

module_init(ofd_init);

module_exit(ofd_exit);

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("Anil Kumar Pugalia <email@sarika-pugs.com>");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Our First Driver");

Above is the complete code for our first driver, say ofd.c. Note that there is no stdio.h (a user space header), instead an analogous kernel.h (a kernel space header). printk() being the printf() analogous. Additionally, version.h is included for version compatibility of the module with the kernel into which it is going to get loaded. Also, the MODULE_* macros populate the module related information, which acts like the module’s signature.

Building our first Linux driver

Once we have the C code, it is time to compile it and create the module file ofd.ko. And for that we need to build it in the similar way, as the kernel. So, we shall use the kernel build system to do the same. Here follows our first driver’s Makefile, which would invoke the kernel’s build system from the kernel source. The kernel’s Makefile would in turn invoke our first driver’s Makefile to build our first driver. The kernel source is assumed to be installed at /usr/src/linux. In case of it to be at any other location, the KERNEL_SOURCE variable has to be appropriately updated.

# Makefile – makefile of our first driver

# if KERNELRELEASE is not defined, we've been called directly from the command line.

# Invoke the kernel build system.

ifeq (${KERNELRELEASE},)

KERNEL_SOURCE := /usr/src/linux

PWD := $(shell pwd)

default:

${MAKE} -C ${KERNEL_SOURCE} SUBDIRS=${PWD} modules

clean:

${MAKE} -C ${KERNEL_SOURCE} SUBDIRS=${PWD} clean

# Otherwise KERNELRELEASE is defined; we've been invoked from the

# kernel build system and can use its language.

else

obj-m := ofd.o

endif

Note 1: Makefiles are very space-sensitive. The lines not starting at the first column have a tab and not spaces.

Note 2: For building a Linux driver, you need to have the kernel source (or at the least the kernel headers) installed on your system.

With the C code (ofd.c) and Makefile ready, all we need to do is put them in a (new) directory of its own, and then invoke make in that directory to build our first driver (ofd.ko).

$ make

make -C /usr/src/linux SUBDIRS=... modules

make[1]: Entering directory `/usr/src/linux'

CC [M] .../ofd.o

Building modules, stage 2.

MODPOST 1 modules

CC .../ofd.mod.o

LD [M] .../ofd.ko

make[1]: Leaving directory `/usr/src/linux'

Summing up

Once we have the ofd.ko file, do the usual steps as root, or with sudo.

# su

# insmod ofd.ko

# lsmod | head -10

lsmod should show you the ofd driver loaded.

While the students were trying their first module, the bell rang, marking the end for this session of the class. And professor Gopi concluded, saying “Currently, you may not be able to observe anything, other than “lsmod” listing showing our first driver loaded. Where’s the printk output gone? Find that out for yourself in the lab session and update me with your findings. Moreover, today’s first driver would be the template to any driver you write in Linux. Writing any specialized advanced driver is just a matter of what gets filled into its constructor & destructor. So, here onwards, our learnings shall be in enhancing this driver to achieve our specific driver functionalities.”

Notes

- In most of today’s distros, one may safely have KERNEL_SOURCE set to /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build, instead of /usr/src/linux i.e. KERNEL_SOURCE := /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build in the Makefile.